Common Resource Rights

What if one person held a monopoly over almost all water?

Achieving that kind of monopoly would obviously be extremely difficult, but it's certainly possible, especially if fresh water were to become much more scarce. Such a monopoly wouldn't have to be global, since it's often impractically difficult for people to move away from certain geographic areas.

It's quite obvious such a monopoly would be equivalent to total authoritarian control over all those who had no other choice than to rely on it, right? I think we can agree a water monopoly would be morally unacceptable, and it would be reasonable for societies to implement rules to make sure that sort of monopoly can't ever happen.

But similar problems arise with much less obvious cases than a near-total water monopoly. What about a land monopoly? Effective land monopolies aren't the stuff of science fiction. We only have to go back a few hundred years to find obvious examples.

In societies such as aristocratic England, it was either forbidden or functionally impossible for people who don't already own land to acquire it. Landowning lords formed an effective cartel that shut out the tenant class, since there was never any reason for the lords to cooperate more with landless people than their landed peers. After all, why compete for the business of people who have nothing you value?

Since tenants had essentially no way to accumulate wealth (any wealth they did accumulate could simply be captured by landlords through higher rents), their position of economic powerlessness was effectively permanent. The tenant class lived at the whims of landlords, and could only survive by somehow making themselves useful, no matter the deprivation and humiliation that entailed.

Economic theory clearly demonstrates that monopoly is dangerous. In order to prove a market is Pareto efficient (that it will lead to situations where no one could be better off without making someone else worse off), the fundamental theorems of welfare economics must simply assume these conditions hold:

- There are no externalities (no agreement between two actors harms another non-agreeing actor).

- Each actor has perfect price information (each knows how much they value something, and how much others value it).

- No actor has market power (no actor or group of actors can force others to pay more than equilibrium price).

Efficient markets are impossible in the presence of monopolies, and will result in pure dead-weight loss in the economy. And the formation of monopolies is an ever-present danger, since it is always rational for agents who can form a cartel to do so. This is of course why most countries have explicit anti-trust and anti-collusion laws.

But monopolies are only one of the tricky problems.

Even perfectly efficient markets can be authoritarian.

The fundamental theorems only guarantee Pareto efficiency, which merely states that no more trades can be made that both actors would willingly agree to. Very worryingly, this includes situations where some actors have nothing of value to trade. Our unfortunate tenants would continue to suffer in their position even if all the laws of aristocracy were abolished and the market was made completely free. A perfectly Pareto efficient market only optimizes trades, not welfare.

Markets aren't mandated by the laws of physics, they're imaginary things constructed by humans to help us cooperate with each other. And the structure we use to construct markets is property rights. You can only voluntarily trade something if you both own it and your ownership is effectively enforced. So if we want to improve markets, we have to somehow change how property rights work.

We have obviously done this to an extent in modern societies. The very idea of public taxation implies that property rights aren't total, which is necessary to prevent situations like a permanently landed aristocracy, or other forms of runaway cumulative advantage. If property taxes are spent in a democratically decided way, then landless tenants can theoretically use them to fund education systems that finally give them some leverage in markets. Anti-trust laws are a similar "exception" to the totality of property rights.

These exceptions to property rights essentially mean that all property is partially owned in common by all members of society, since some fraction of the value of private property is gathered together and allocated democratically. Hence partial common ownership.

However our property taxes and anti-trust laws are very difficult to properly define and enforce:

- Property taxes must be based on the value of the property, but in most places that value is simply assessed by a government official. These officials can easily be deceived, or simply operate on flawed models that don't accurately assess reality.

- There are some ways to measure market power, but they're very complex and difficult to have confidence in, so legally defining anti-competitive behavior is an extremely slippery task. And even good anti-trust laws are difficult to enforce, since once an entity has become large enough to merit anti-trust intervention it has almost always already gained a dangerous amount of power. By the time you're legally allowed to do anything, it might already be too late.

Simply, property taxes and anti-trust laws aren't actually achieving true partial common ownership. Property taxes certainly haven't prevented the formation of a cartel of millions of homeowners. This kind of "lazy monopoly", where a property owner unproductively holds an asset hostage while they watch it increase in value, prevents true partial common ownership and is an inevitable consequence of non-negotiable property.

Non-negotiable property isn't most efficient or most ethical. Our common idea of property ownership essentially enshrines the "dibs" rule as a sacred right, makes big and small monopolies inevitable, and reinforces cycles of cumulative advantage through the "property ratchet".

In contrast, all of these problems are by definition completely avoided if we can somehow ensure all property is always fulfilling its "highest and best use" from the perspective of social welfare.

But how do we figure out some property's highest and best use? Different people want different things, and it seems basically impossible for even an altruistic central planner to correctly balance everyone's different valuations of different things.

The clever concept of Harberger taxes almost solves the problem, but needs to be smoothed out using Adaptive Democracy. First let's explain how Harberger taxes work.

Harberger taxes

Harberger taxes achieve highest and best financial use for resources (called allocative efficiency). Here's how it works:

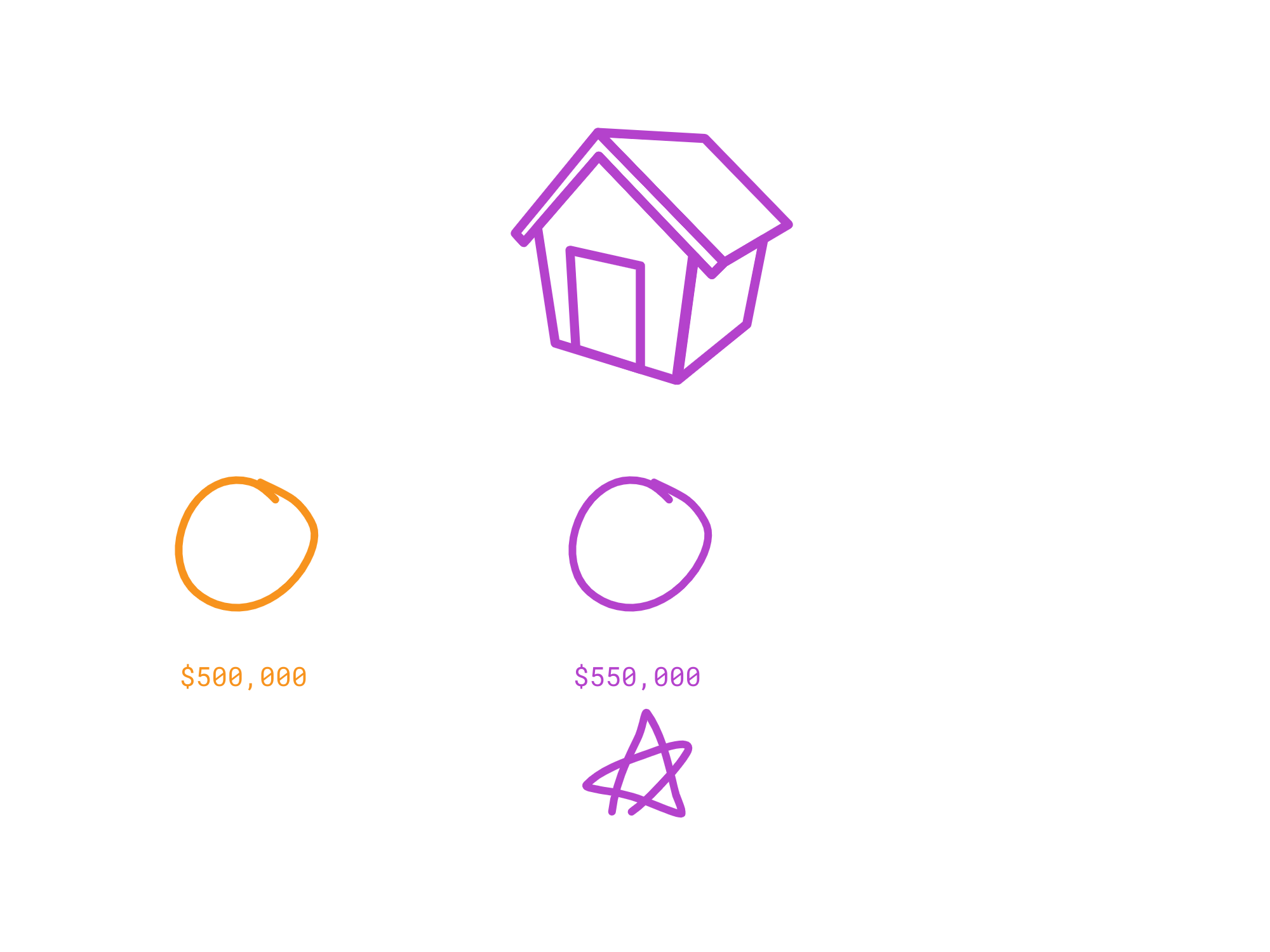

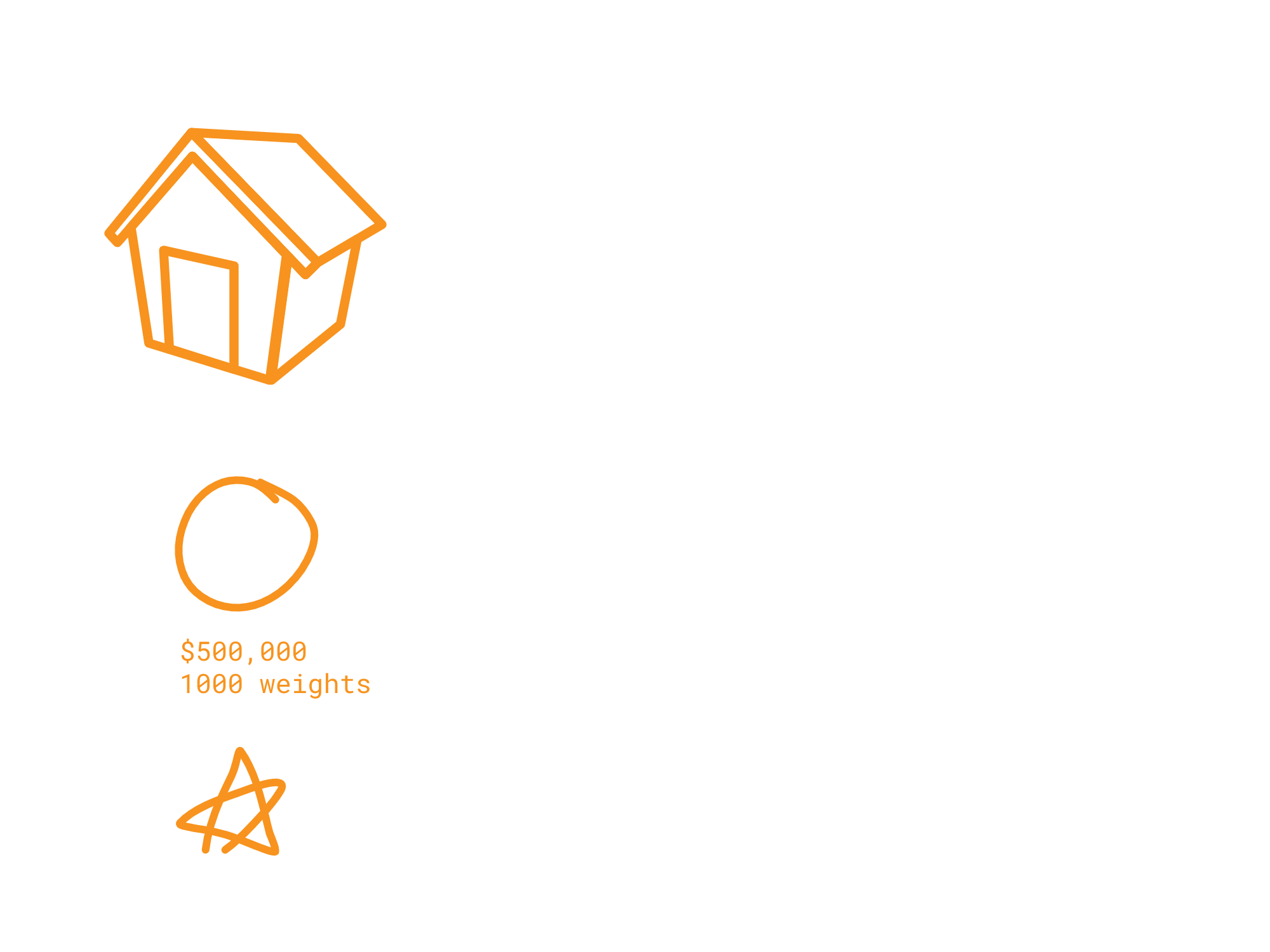

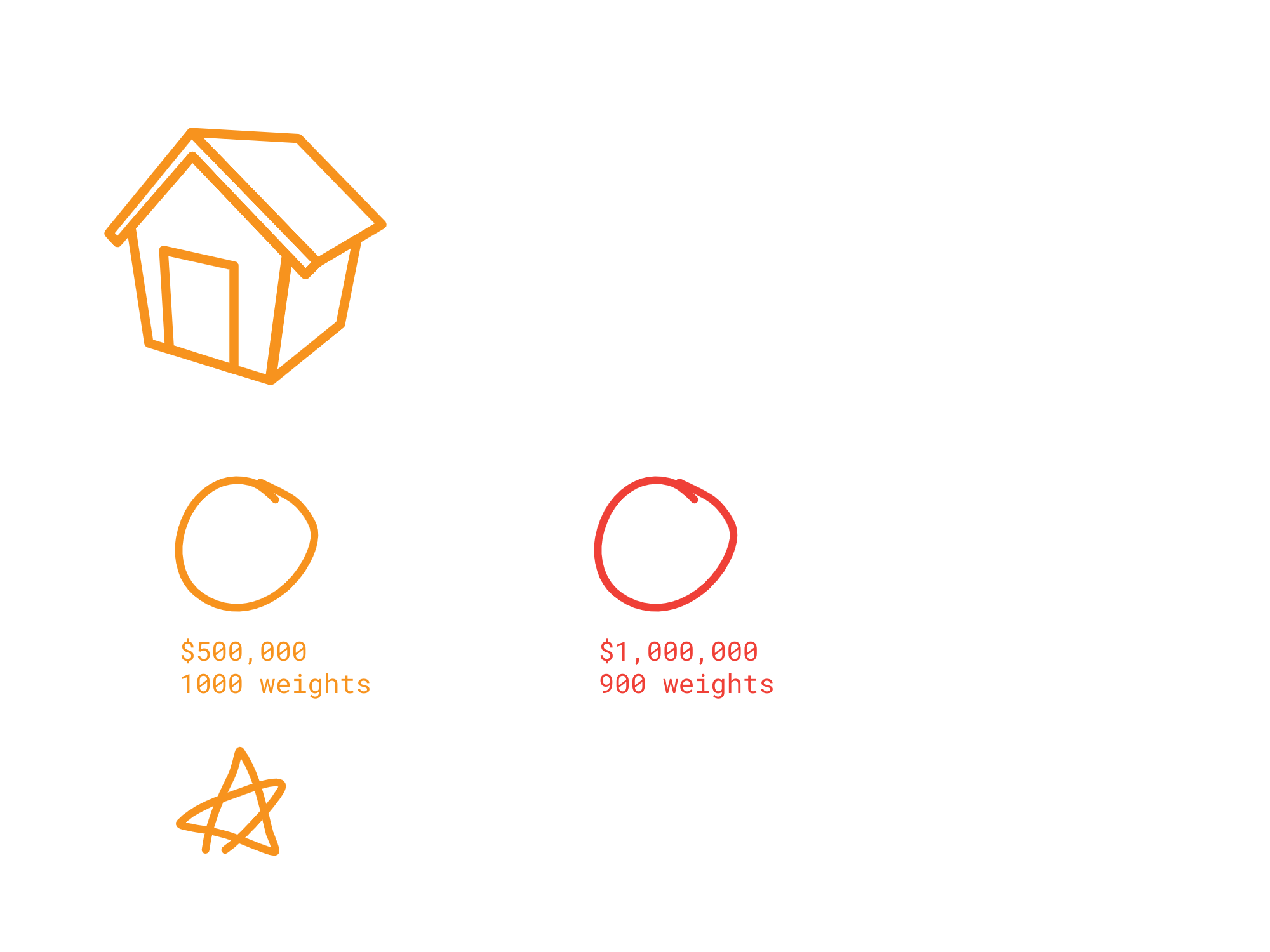

- If someone owns something, they state their own self-assessed value, basically how much it's worth to them (such as $500,000 for a house). Their property tax is some percentage of that self-assessed value (such as 1% per year).

- What's to stop them from giving a really low price to avoid taxes? If someone comes along who's willing to state a higher price, the owner must sell it to them.

This system is clever because it perfectly incentivizes all owners to state their value honestly, and ensures the property is always owned by whoever values it most. This makes things like monopolies structurally impossible.

However, this system only values things financially. Every piece of property would only be valued based on its ability to generate financial returns, and all the other kinds of value (beauty, stability, culture, health) would only be able to survive by somehow being tied to commerce.

I don't think it's controversial to say such a system would be an inhumane nightmare. Markets are tools to support the welfare of human beings, not the other way around.

However we can still get the efficiency of Harberger taxes by combining them with Adaptive Democracy.

Common Resource Rights

Common resource rights are essentially Harberger taxes combined with Adaptive Voting.

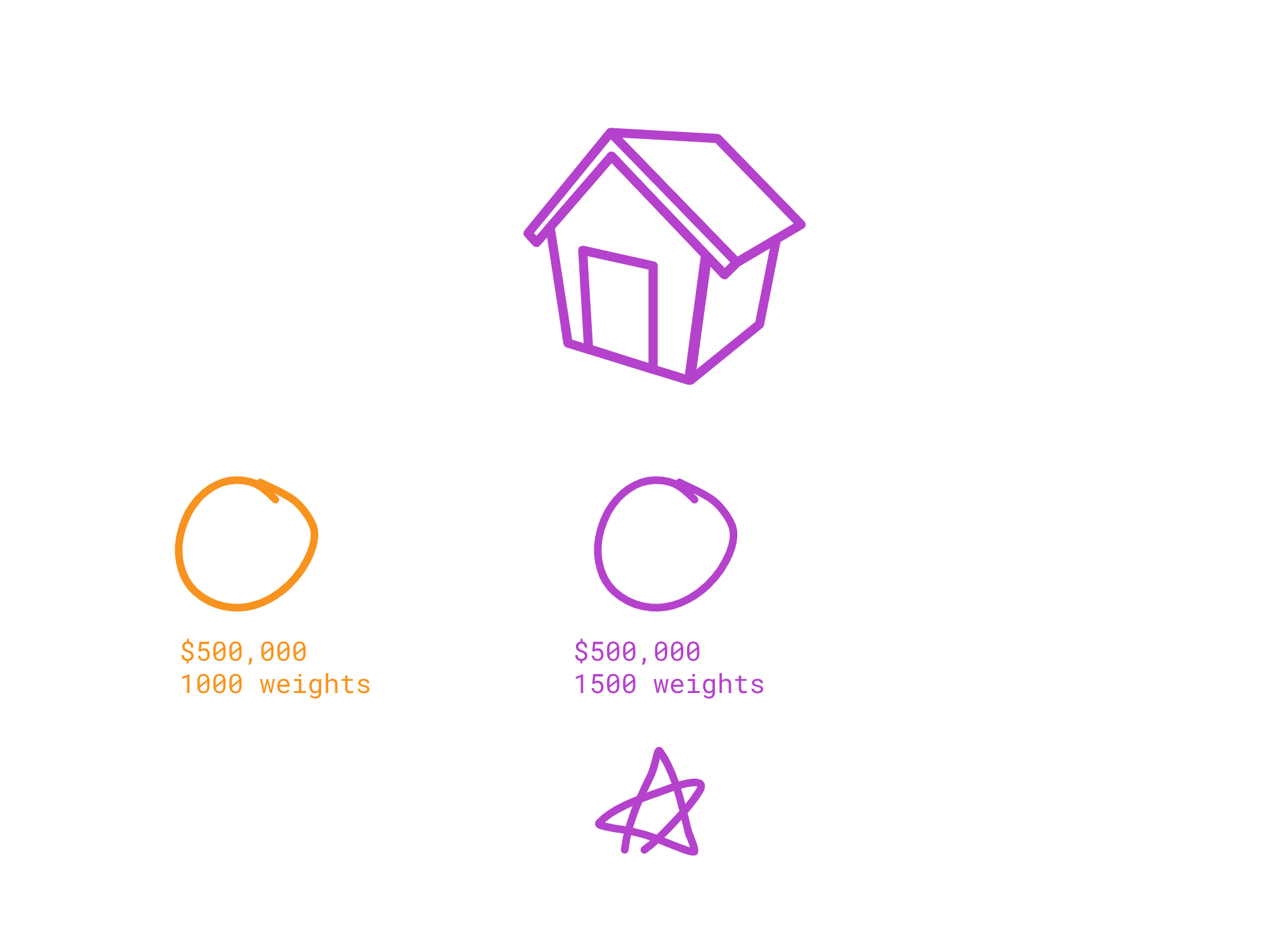

- Owners would still state a monetary price for property, but could also include some voting weights.

- In order to become the new owner, someone has to match one and beat one. Their offer has to be strictly stronger when combining both monetary price and voting weights. If someone offers more money but not as many weights, their offer is rejected.

- But if someone matches one and beats one, they become the new owner.

Offers are stabilized just like in Adaptive Voting, so if someone makes a stronger offer the current owner has time to increase their price. We don't want people who genuinely value something more than they realized to be forced to give it up. Besides, even with a pure Harberger tax an out-offered owner can immediately turn around and use the sale money to make a counteroffer. Using stabilization periods keeps this process from being wasteful and irritating, gives owners time to prepare to transfer the property in the event they decide to sell, and pushes all offers to be serious.

Since offer weights would be quadratically scaled, more strength is given to offers made by larger groups, meaning socially valuable uses are given an advantage. This is a good thing, since social value is the actual goal of markets, whereas profit-motivated commerce is just an indirect gamble at creating social value. This system even makes it possible for someone to hold property with nothing other than voting weights, meaning they don't pay any property taxes at all.

A few common worries are easily addressed:

- Can someone buy only my left shoe?

You can "bind together" property so it has to be bought as a package. - Are national parks up for sale?

Constitutions can use democratic districts to set aside protected areas.

How would this change society?

By including voting weights in offers, we've obviously prevented some of the most scary outcomes (billionaires can't just buy the entire world). But some questions deserve more thought.

- Will normal people get caught in nasty bidding wars, throwing each other out of their homes?

No, since this system would make new housing construction basically inevitable, especially if we had better systems for funding public goods. There are many people who are unsatisfied with their living situation, and these people could band together into cooperatives to purchase either their existing neighborhoods or underused land and build much nicer communities for themselves (the next chapter will discuss cooperatives extensively). - Would landlords even exist anymore?

Hopefully not! Landlords are purely extractive middlemen who add no value to society. Importantly, managing property isn't the same as owning it. The useful skills offered by property managers can just as easily be employed by owner-occupiers as absentee landlords. - Would billionaires even exist anymore?

Possibly not! Despite what market absolutists say, markets don't directly reward "solving problems" or "innovating", they only directly reward owning property. In a market with increasing returns to scale, property ownership is a ratchet that creates cumulative advantage. It seems unlikely that becoming a billionaire demonstrates some massively unusual contribution to the economy, but instead the cunning to see points of vulnerability and how to use property to pry them open. Read the chapter on intellectual property and assurance contracts to think about how we could much more directly reward invention. - Could this even apply to resources in outer space?

Yes! This system of ownership negotiation would scale elegantly as we increased its range, since newly possible property would start out valued at$0and0 weights, available for anyone to claim. When combined with democratic districts, it's possible to elegantly manage an arbitrarily large area with arbitrary flexibility. - Would prices drop dramatically?

Yes they would. This is largely a good thing, but we would definitely need a way to transition to this system that wouldn't shatter all the plans of existing property owners. The idea that seems simplest and most effective is simply forgiving some amount of loans beyond whatever price property settles at some period after the transition. Read here for more thoughts.

Since this would be such a massive change, it probably shouldn't happen all at once. There are a few types of assets we should target first since they would be much less difficult to transition, such as bands of electromagnetic spectrum, internet domain names, public parking spaces, emissions licenses, and intellectual property deeds such as patents and copyrights.

I hope you can see how much a system like this would improve both the social welfare and productive efficiency of our society. Both social and financial value would tend to separate into different areas and both would have the opportunity to flourish and access the resources they need most.

If your reaction to this idea is that it would impinge on the freedom of the market, I invite you to take a second look at what markets actually are. Again, markets aren't laws of nature, they're human creations intended to help us cooperate and achieve shared goals. Harberger taxes achieve provably optimal allocative efficiency while still maintaining investment efficiency, and the modification to common resource rights is so structurally similar it's very likely to do the same for welfare (work-in-progress proof sketches).

Here are some relevant detail chapters for those interested in diving deeper.

- What is Quadratic Voting/Funding, and why does it work?

- Adaptive Constitutions and Democratic Districts

- Public Goods and Cooperative Goods

- Intellectual Property and Assurance Contracts

- Toward Verified Foundations for Ethics and Democratic Coordination

Otherwise, let's talk about cooperatives!